In the age of digital dominance, electoral bonds are a calculated and sophisticated step towards electoral gain.

Money is never neutral but it tends to mostly, if not always, favour the most domineering and deep-pocketed.

This expression is highly relevant in the context of Indian elections where the stakes are always high and the sole agenda of our political class is to win elections in order to amass more money for the party and future elections. ‘Anything and everything’ is justified in order to win. What is left behind in this whole gimmick of money and power play is a credible, honest, worthy leader and citizens who are reduced to only voting once in five years.

After a wait of more than six years, the five Judges Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court of India heard the petition challenging the amendments brought by the Finance Act, 2017 for three consecutive days and in the end, reserved its verdict.

Whereas India is moving towards a more opaque political finance regime, global standards show that private funding is more regulated now and provisions have been made to provide greater access to public funding. According to the International IDEA (Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance), more than 50 per cent of the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) member countries have banned anonymous donations to political parties. All anonymous donations to parties are banned in some 16 OECD countries whereas in 15 countries, anonymous donations are banned above a certain threshold.

In India, we not only have unlimited unchecked anonymous (corporate) donations but the government has also opposed citizens’ right to know the sources of political funds. The inability of the voters to identify who funds parties’ election campaigns and to conduct a thorough fact-check on the antecedents of the parties directly infringes on their right to informed voting, and free and fair elections.

Argument 1: Amendments were brought in to reduce political donations being given in black money.

Rebuttal: Contrary to the above assertion by the Government, the Electoral Bonds Scheme legalises backroom lobbying and unlimited anonymous donations by allowing foreign entities, large-scale entities, unknown hidden entities, and benami transactions to funnel unaccounted black money through shell companies. They steadily legalised and institutionalised the use of unaccounted illegal money. Any corporate or individual could now hand over any amount of unaccounted money secretly to a political party. Moreover, in the age of digital dominance, the electoral bond is a well-calculated and the most sophisticated step towards electoral gain and turning black money into white.

Argument 2: Amendments do not infringe citizens ‘Right to know’ as citizens have no right to know about financial bearings of political class.

Rebuttal: The Attorney General of India in his submission before the Constitution Bench had stated that citizens have no general right to know about anything and everything about the funding of political parties. This claim by the government not only fails the test of constitutional propriety but such a stand also undermines the value and crucial role played by the citizens in a participatory democracy.

Labelling citizens’ ‘Right to know’ as ‘general’ and crucial information under such right as ‘anything and everything’ is rather sad and evidently shows the government’s clear motive to stifle citizens’ voice and right to audit actions of the political class. The government, political parties and the donors would always know about the donations made through the Electoral Bonds Scheme, it is only the common man who will be kept in the dark with no say whatsoever in the electoral democracy.

The Supreme Court through its various pronouncements has already given due acknowledgement to citizens’ Right to Know, who act as a watchdog. In Secretary, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India and Others v. Cricket Association of Bengal and others [(1995) 2 SCC 161] that “One-sided information, disinformation, misinformation non-information all equally create an uninformed citizenry which makes democracy a farce when medium of information is monopolised either by a partisan central authority or by private individuals or oligarchic organisation.” In State of Uttar Pradesh v. Raj Narain and Others [(1975) 4 SCC 428], the Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court had clearly held that,” The people of this country have a right to know every public act, everything that is done in a public way by their public functionaries. They are entitled to know the particulars of every public transaction in all its bearing.”

Argument 3: Any possibility of quid pro quo between corporates and political parties under the amendments is very rare.

Rebuttal: Every word used in the Finance Act, 2017 points a needle of suspicion toward the quid pro quo arrangement between the government of the day and corporate entities. Political parties and politicians will gloriously respond to incentives given by a corporate entity. It is no secret that a business or corporate entity that donates to a political party sees it as an investment where a healthy return on the investment is expected.

There is no legal requirement to disclose the details of donee political party (ies) and the bifurcation of the total amount contributed to political donations. More layers to opaqueness have been created, as bearer electoral bonds are designed by the Union government in a way that the money can secretly pass several hands to reach the ultimate beneficiary, that is, the political party.

While recently many countries like Brazil and Germany have completely banned corporate donations, in India it has been firmly institutionalized since 2013. Whether it is donations from companies via electoral trusts or unlimited and anonymous donations through electoral bonds, or through shell companies, foreign sources etc, the flow of money should never stop. It is a grim reality that Indian laws have allowed this free flow of money into our electoral and political process, so much so that it is mainly the cash that does the talking, rather than the labour of the lawmakers who are primarily appointed by the citizens for the betterment of their future.

Argument 4: Electoral Bonds and the electoral level playing field.

Rebuttal: The government argued that disproportionate donations in favour of the incumbent party have always been a reality. This may be true, but with the introduction of Electoral Bonds, the inequity has become even more stark. Since the inception of the Finance Act,2017 many contestants of undoubted ability and credibility have been eliminated from the electoral contest.

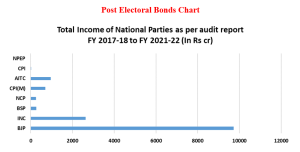

In free and fair elections, the term ‘fair’ denotes ‘equal opportunity to all people’ and electoral bonds have corroded the concept of ‘equality of treatment and opportunity’. Most of the donations received through electoral bonds go to the ruling party at the centre. The rest is taken by other parties dominant in various states. As per ADR analysis, since the inception of the Electoral Bonds Scheme, more than 52% of BJP’s total donations came from Electoral Bonds worth Rs 5271.9751 cr, while all other National parties amassed Rs 1783.9331 cr. Instead of seeing this as inevitable, any future regulations on political funding must try to fix this.

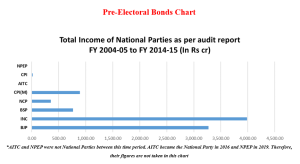

(Click on the charts to view them.)

Argument 5: “….The operations of the Scheme are not behind iron curtains incapable of being pierced. All that is required is a little effort to cull out such information (Electoral Bonds contributed to parties by Corporate donors) from both sides i.e. the donor and the donee and do some match the following”.

Rebuttal: We selected a sample of the top 47 corporate donors to three major National Political Parties in FY 2020-21. We tried to access their annual reports on the Ministry of Corporate Affairs website (as suggested by the government) and found out that it requires you to pay a fee for viewing the documents per company for a limited period of three hours. There are 23,33,958 registered companies as of April 2022. It is unreasonable for the government to expect citizens to go through the annual reports of these companies by paying the aforesaid fee, to ascertain which company made donations through electoral bonds.

Moreover, as the donor faces no obligation to report the name of the political party to which it donated bonds and the recipient—the political party—need not disclose the donor’s identity, it is impossible to do this “match the following”.

The steps taken by the government to safeguard the confidentiality of the companies over the larger public interest of its own people are worrisome.

Argument 6: Amount of Unknown Sources of Income (declared by parties in their audit reports but without giving their source) has reduced since Electoral Bonds.

Rebuttal: It is important to understand that these bonds also come under the definition of Unknown Sources. In the five years since their inception, the total income of only National Parties from such sources was Rs 9217.86 cr, as opposed to, Rs 6612.42 cr between FY 2004-05 to 2014-15. Between FY 2017-18 and 2021-22, National Parties’ income from Unknown Sources increased by 198%.

It was also argued that the voluntary contributions (below Rs 20,000), the details of which are not required to be disclosed as per law have come down since electoral bonds were introduced.

However, the latest data available on the Election Commission’s website for FY 2021-22 and 2020-21 shows otherwise. Between these two years, such donations increased from Rs 171.1957 cr to Rs 199.4951 cr. For the ruling party at the centre, it rose from Rs 78.044 cr to Rs 127.104 cr.

It is therefore ironic that instead of encouraging transparency in political funding, such scrutiny is seen as a burden and interference by the government and political class.

In such a scenario, citizens can only rest their expectations on the Supreme Court verdict and hope that the court realises the present predicament and declare the Finance Act, 2017 unconstitutional. One can only hope for an evolving, if not ideal, democracy where every single public action is done in a public way by public functionaries.

This article has been written by Ms Shivani Kapoor (Program Lead and Manager – Legal – at ADR) and Ms Shelly Mahajan (Program and Research Officer – Political Party Watch – at ADR). It was originally published in The Quint.