The heading of my column is, obviously, an adaptation of a famous sentence written by Ian Fleming, creator of the iconic spy, James Bond. The same series had one more film titled Licence to Kill. It is a strange coincidence that while James Bond supposedly had the licence to kill the bad guys, it may well be said that India’s electoral ‘Bond’ seems to have the licence to kill democracy!

Electoral bonds had a very auspicious beginning. The then finance minister, while introducing the Budget on February 1, 2017, introduced electoral bonds as a panacea “to cleanse the system of funding of political parties”. However, the same afternoon an indication came that there might be something more than met the eye when the minister said during his customary media interaction that “these bonds will be bearer in character to keep the donor anonymous.”

Subsequently, when details of the Finance Bill were made available it became clear that electoral bonds were a subterfuge to make electoral and political funding completely opaque. This was proposed to be done by amending three Acts — the Representation of the People Act (RP Act), Income Tax Act, and the Reserve Bank of India Act. It took the government almost a full year to notify the scheme on January 2, 2018. On the face of it, the scheme looks harmless. But it has several stipulations, the implications of which are not obvious. A couple of examples follow.

Section 29C of the RP Act requires political parties to make annual declarations of contributions received from individuals and companies in excess of Rs 20,000 each to the Election Commission of India (ECI). The amendment to this section says that the following shall be inserted, “Provided that nothing contained in this sub-section shall apply to the contributions received by way of an electoral bond.” In simple terms, it means that political parties will not be required to disclose and declare any amount received by way of an electoral bond. Does this increase transparency or reduce it?

Section 13A of the Income Tax Act says “Special provision relating to incomes of political parties” which gives political parties 100 percent exemption from income tax. Only those parties are eligible for this exemption who “keep and maintain a record of such contribution and the name and address of the person who has made such contribution … in excess of Rs 20,000”, and submit this information to the ECI.

The operative part of the amendment to Section 13A says that “after the words ‘such voluntary contribution’, the words ‘other than contribution by way of electoral bond’ shall be inserted”. The real impact of this amendment is that political parties do not need to disclose donations by electoral bonds even to the Income Tax department.

Even more damaging are the amendments to the Companies Act. Sub-sections (1) and (3) of Section 182 of this Act stipulated that (a) a company could not contribute more than “seven and a half per cent of its average net profits during the three immediately preceding financial years” to any political party; and (b) a company making donations to political parties was required to disclose “particulars of the total amount contributed and the name of the party to which such amount has been contributed” in its profit and loss account. Both these requirements have been removed by the amendment of the Companies Act with the introduction of the electoral bonds scheme. The result is that now there is no limit to how much money a company can donate to political parties, and the names of the parties do not have to be revealed.

The most damaging aspect of electoral bonds is their potential to choke funding for all opposition parties, and channel all the funding to the ruling party. This is likely to hold regardless of which party is in power.

Here is how it works. The State Bank of India (SBI) collects “Know Your Customer” (KYC) particulars of the buyers of electoral bonds. While the explanation to the Electoral Bonds Scheme says that SBI will not share this KYC information with anyone, it defies common sense that any information with SBI will not be accessible to the finance ministry. And if the ministry is aware of something, then it is accessible to the ruling party. And once the ruling party knows who has bought electoral bonds, it is no rocket science to figure out how the party in power can “persuade” or “cajole” the buyer of electoral bonds to donate these bonds to itself.

An apprehension voiced when electoral bonds were introduced was proved to be justified by data from the financial year 2017-18. Electoral bonds worth Rs 222 crore were purchased in FY 2017-18. The 2017-18 annual audit report submitted by the BJP to the ECI showed that the party received Rs 210 crore worth of contribution in the form of electoral bonds. This means that 95 percent of all the electoral bonds purchased in 2017-18 were donated to the ruling party.

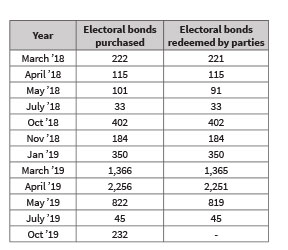

With Rs 6,128 crore donated to political parties between March 2018 and October 2019, it is clear how much money from unknown, and possibly unaccounted, sources flows into the political and electoral systems. The spike in the purchase of these bonds just before and during the 2019 Lok Sabha elections is also worth noting.

Problems with electoral bonds have been placed before the Supreme Court. The Court, in an interim order on April 12, 2019, said that “the rival contentions give rise to weighty issues which have a tremendous bearing on the sanctity of the electoral process in the country. Such weighty issues would require an in-depth hearing which cannot be concluded and the issues answered within the limited time that is available before the process of funding through the electoral bonds comes to a closure, as per the schedule noted earlier”.

The “process of funding through the electoral bonds” came “to a closure” a long time ago but the Supreme Court has not taken up this issue so far.